Natural-Language Server Management With Opencode + SSH #

For years I’ve wanted this.

Ever since LLMs became popular in 2021, one question has remained in my mind:

“Why can’t I just talk to my servers?”

Something like:

-

“List open ports on big-pc.”

-

“Clean up Docker on that server-2.”

-

“Generate me a markdown report of the findings.”

And the AI just… does it.

Not via some giant automation framework.

No YAML.

No agents.

No GitOps stunts.

Of course we can already do that to our own computer: MCPs, Warp terminal, Termbot, etc. But not for remote servers. The idea is simple and elegant: Just a tiny local tool, an LLM, and SSH.

This week, I finally built it by using opencode.ai .

And honestly?

It took me a while to figure it out, but it turned out to be way easier than I expected. And it works better than I expected.

The Setup (Surprisingly Small) #

If you don’t know what Opencode is, it’s a direct alternative in terms of CLI AI code assistants to Claude Code, Gemini Cli, except that it’s Open Source, and completely BYOK (Bring your own key). And, if we zoom out a bit, it’s also an alternative to Cursor, Windsurf, etc. GUI applications.

I’m sure we can accomplish the same thing in Claude or Gemini by following the same philosophy. However, the rest of this post is the implementation specific to Opencode.

For this, I’m using Tailscale but it doesn’t really matter as long as we have direct access to our remote servers.

Also, this process assumes the usage of Public keys in SSH, since we’re not dealing with SSH password prompts.

Instructions #

First we need to set up NPM and install a known package called execa (So Node.js can interact with our shell). That way, Opencode can execute shell commands (In this case, SSH) “globally”.

cd $HOME/.config/opencode/

And inside that folder:

npm init -y

npm install execa @opencode-ai/plugin

And also a normal .ssh/config entry containing the specific servers we want to remote to:

Host test-server

HostName <TAILSCALE_IP_ADDRESS>

User user

which allows to use SSH and a representative name of the server in the first place:

ssh test-server

This way, if the prompt given to Opencode involves “Executing X on test-server”, the LLM will just perform “ssh test-server” which simplifies the process as much as possible.

And, if our prompt creates commands that require sudo, we can specify the Sudo password in an environment variable:

export OC_SSH='<your-password>'

Seems very unsafe, but I talk about the implications on that later in this post.

That’s it.

No agents.

No credentials in prompts (The LLM won’t ingest this environment variable).

No secrets in code.

The Tool #

“Tools”, in Opencode, are similar to Claude Code’s “Plugins” - Basically adding “skills” to our LLMs with Typescript declared “integrations”.

This is the entire thing:

The file we need is: $HOME/.config/opencode/tool/remote.ts

import { tool } from "@opencode-ai/plugin";

import { $ } from "execa";

export default tool({

name: "remote",

description: "Execute a command on a remote server via SSH.",

args: {

target: tool.schema.string().describe("The hostname alias (e.g., 'prod-db')."),

command: tool.schema.string().describe("The command to run."),

},

async execute({ target, command }, context) {

try {

let output;

const isSudo = command.trim().startsWith("sudo");

if (isSudo) {

const sudoPass = process.env.OC_SSH;

if (!sudoPass) {

return "ERROR: You tried to run 'sudo', but I don't have the 'OC_SSH' environment variable set locally.";

}

const safeCommand = command.replace(/^sudo/, 'sudo -S -p ""');

output = await $({ input: sudoPass })`ssh -o BatchMode=yes ${target} ${safeCommand}`;

} else {

output = await $`ssh -o BatchMode=yes ${target} ${command}`;

}

if (output.stderr) {

return `WARNINGS:\n${output.stderr}\n\nOUTPUT:\n${output.stdout}`;

}

return output.stdout;

} catch (error) {

return `SSH ERROR on ${target}: ${error.message}`;

}

},

});

The important part:

- The LLM never sees the password.

- sudo is optional

- The password is injected into stdin, not the prompt.

- And nothing is ever returned or logged.

This creates a clean one-way flow:

The AI just sees the stdout from the remote server.

The First test: When it all clicked #

For this “demo”, I decided to perform a 2-fold “process” with this tool:

- Ask it to run Lynis with

sudo(CISOfy’s Linux auditing tool), which I recently installed on the remote system - Read the Lynis report, and generate a local summary of it, on my host.

In the following screenshot, I call opencode as CLI, not as TUI. I aliased “oa” to opencode ask so it’s more direct:

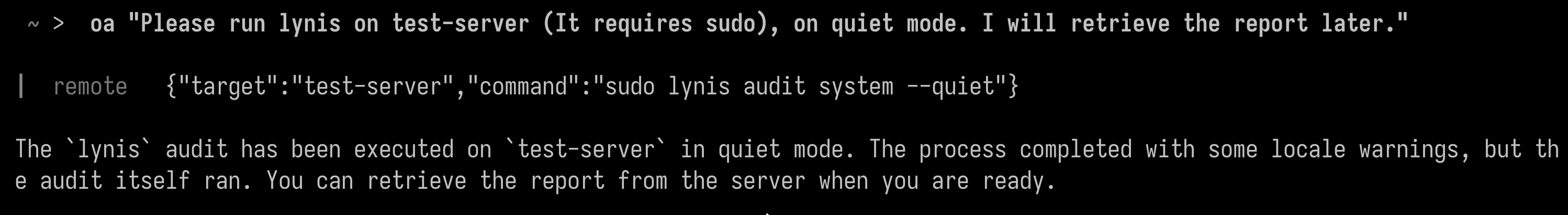

(“Please run lynis on test-server (It requires sudo), on quiet mode. I will retrieve the report later.”)

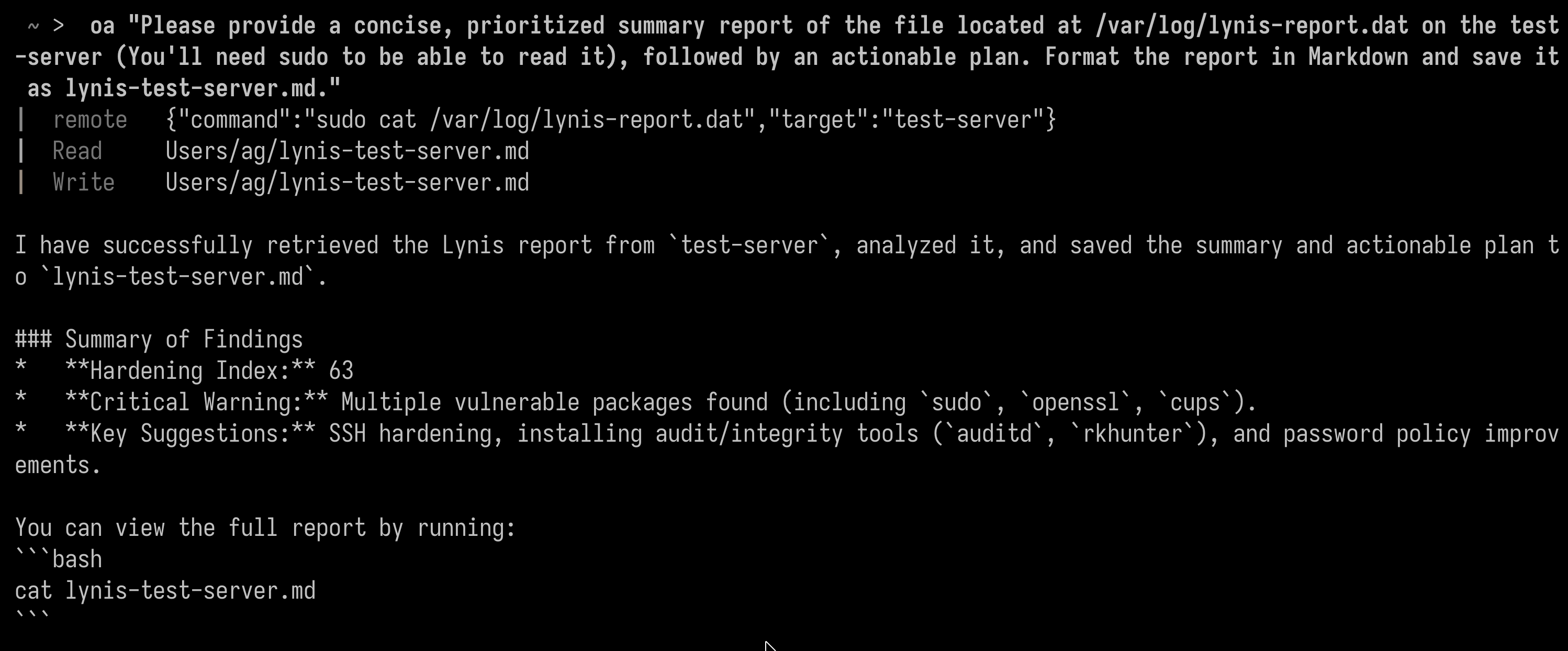

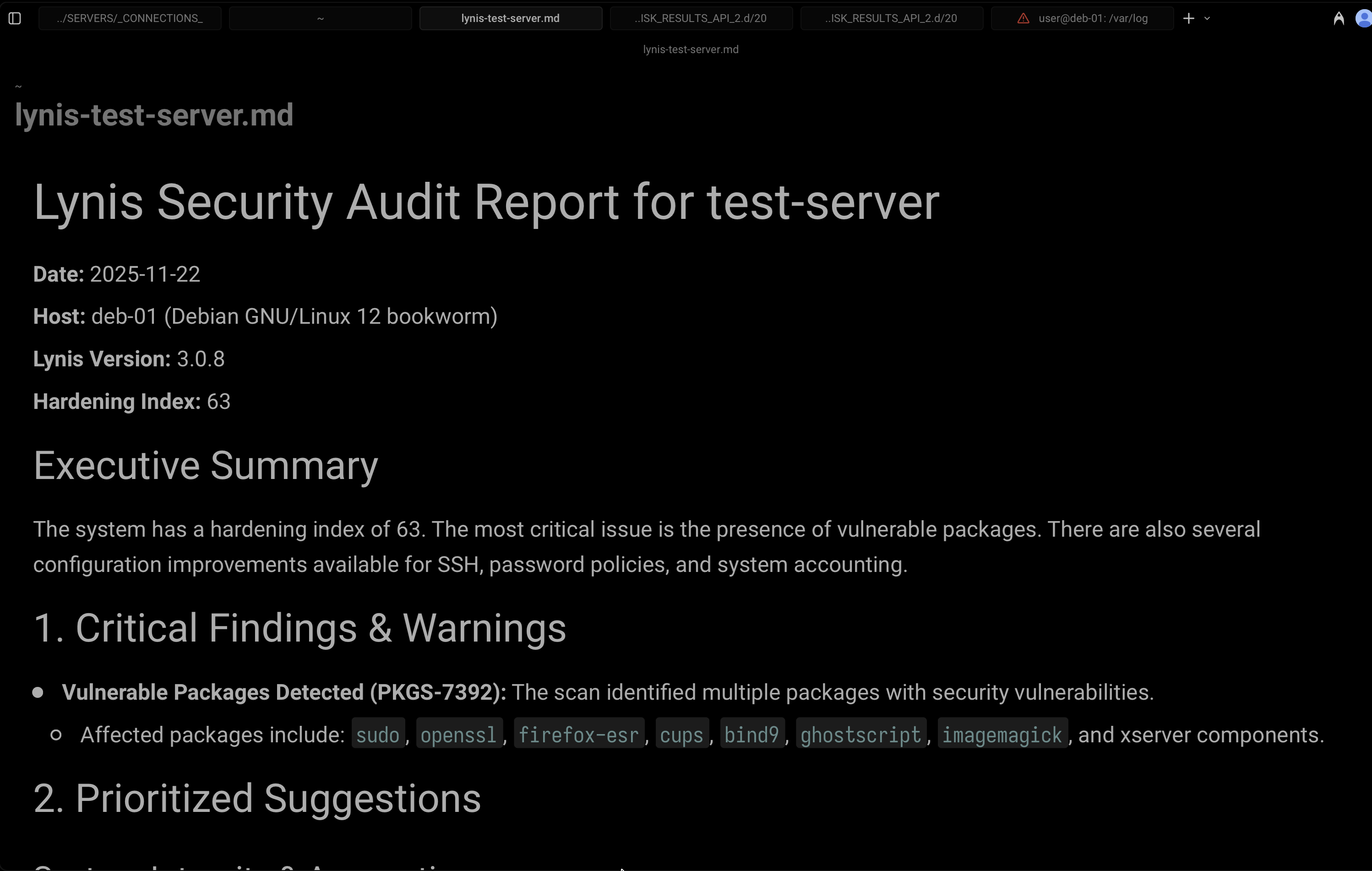

And then, ran it again, but this time asking it for a Markdown report of the Lynis results (Sudo access also was needed):

“Please run lynis on test-server (It requires sudo), on quiet mode. I will retrieve the report later.”

Beautiful.

Here’s how it looked:

I can’t explain how satisfying this felt.

Natural Language Operations #

From this point, I realized:

this isn’t “automation”. it’s something simpler and way more flexible.

I can literally type:

oa "Shutdown test-server"

or:

oa "Update system packages on server-33 and check for leftover services"

or:

oa "Create a crontab on big-pc that runs Lynis weekly and saves the report to /var/log/lynis-weekly.log"

And it just does it.

There is no playbook, no YAML, no boilerplate.

It’s just me talking to my lab.

Security Considerations #

- No, the LLM never sees the SSH user’s sudo password. It stays in an environment variable that gets passed to the SSH command directly. However, there can be potential leaks in some scenarios.

- Use your judgment when pulling data from a server. The LLM only sees the stdout/stderr of the remote command. If you ask it to dump config files, logs, secrets, environment variables, DB credentials, etc., it will happily summarize them for you. That’s instant compromise of data. Avoid feeding the model sensitive server output.

- Although it’s rather rare that an LLM hallucinates a wrong command and ends up screwing you, it’s better to prefer high level ops.

- Know what you’re doing. If you’re unsure of the consequences of what you’re asking it to do, then don’t do it. Research it first.

- Avoid running this “against” untrusted hosts. The threat is high impact, but very low likelihood.

- I’m not sure of the implications of sending commands, and this “agent” deciding to perform iterations if it finds issues. In other tests, it just keeps SSHing into the remote machine to perform commands until it accomplishes the task. And that’s dangerous, but I haven’t figured out yet how to make Opencode ask for my permissions or validation (There seems to be an error with custom tools where the “ask” permissions parameter in the config file get ignored).

- This system can run arbitrary SSH commands, but that’s on you, the user. Again, it’s unlikely that your prompt will be misunderstood into an SSH backdoor or data exfiltration, but it’s still a potential threat.

This system is perfect for a personal lab or internal testing, not PCI workloads or sensitive customer environments. It’s a convenience tool. Trate it as such.

What’s Next #

I’ll probably create a small GitHub repo with these tools and start adding more “verbs” over time.

But the core idea stays the same:

-

*Talk to your servers.

-

*Let the AI do the boring part.

-

*Stay in your chair.

Honestly, I LOVE this little setup.

It’s simple, it’s relatively safe (Although it requires a lot of testing and threat modeling), and it’s exactly the kind of thing I wished I had since 2021.

If you want the code, I’ll probably put it on GitHub in a few days, but the whole thing fits in one file anyways.

Closing thoughts #

There must be an opportunity for making a similar tool but for Ansible because this current implementation is for 1 server at a time (1 prompt at a time). I’ll keep testing in the next days.

I’ll also be red teaming this system to explore the potential leaks and vulnerabilities that it might have (i.e. prompt injection from the remote host).

If you have some ideas, please let me know!